Within the cluster in the hive, honeybees maintain a temperature between 92°F and 95°F year-round. They do not hibernate. They do not migrate. They hunker down and create kinetic heat by vibrating the same thoracic flight muscles that normally beat their wings. They are able to detach the wings and vibrate to produce heat even when they have tucked themselves inside a cell within the cluster. Vibrating these wing muscles between 200 and 250 times per second, collectively, the colony is able to create enough heat to raise new bees in the area we call the brood nest even in the depths of winter.

This shouldn’t be too much of a surprise if you stop to think about what has to happen to make the yearly cycle work. Suppose a colony, to effectively harvest the abundant nectar of spring, needs 50,000 workers on the job April 1. Upon winter solstice, December 21, they are at their smallest population for the year, perhaps as little as 6,000. This is to stretch their winter stores—less mouths to feed. So, between the New Year and April 1, they might need to raise 40,000 new bees just in preparation for the nectar flow. Plus, they have to replace any bees that die off during winter freezes. That’s about seven new bees for every living bee in the colony. This will take some time. They can’t wait to the last minute to get started.

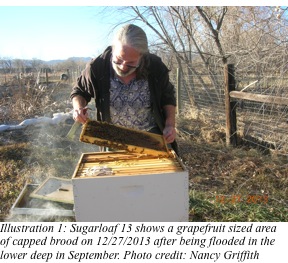

It takes 21 days to raise a worker from egg to emerge. Although the queen is capable of laying 1,000 eggs in a day, she cannot produce more eggs than can be successfully warmed with the current population of workers. That means early in the year, the brood nest might be the size of a golf ball and contain 100 or 200 new workers in progress. Every day a few more eggs are laid so there are always bees in progress. Once they emerge, the nest will grow using the heat from the extra bodies. By March, the queen should be laying at full capacity because spring is just 21 days away.

Winter and summer bees are physiologically different. They have different proteins in their hemolymph (blood). Late summer and into fall, the bees are raising the workers that will live through winter. Summer workers are dying off, and a smaller cluster is prepared for the cold months ahead. These winter workers are fatter than their summer sisters, and they will live substantially longer—120 to 180 days—compared to a summer worker at 45 days. Their entire life is dedicated to two activities. They shiver to create heat, slowly working their way into the center of the cluster where they are toasty warm and fully mobile. Then they use that heat and mobility to make a trip to the food, eat, and join the cluster again at its outer mantle. There, they begin again to shiver. That’s it: shiver, eat, shiver, and eat again.

Today’s headlines are about crops being damaged due to the frigid temperatures. Warnings about wine, citrus, even cattle are everywhere. Growers are anxiously awaiting news of their fate.

The good news is that there are honeybees that know how to deal with these temperatures. They’ve been doing it for thousands of years. I’ve got a lot of living honeybees, and I’m looking forward to my best year ever. If the blossoms can survive the arctic cold, then I’ll have honeybees ready to harvest the nectar. Yes, it’s a bit early for me to be so optimistic with the majority of winter still in front of me and four colonies already dead. But it seems farmers are an optimistic bunch, and I guess I’m one of them, or more correctly, I guess I’m a rancher because honeybees are considered livestock.

Get self-health education, nutrition resources, and a FREE copy of A Terrible Ten: Health Foods That Ain't ebook.

Get self-health education, nutrition resources, and a FREE copy of A Terrible Ten: Health Foods That Ain't ebook.

That’s fascinating to know. I always thought they hibernated! This is far more interesting. Thank you so much for your detailed facts!!